Interview with Yukihiro Ohta,

a Japanese potter in MashikoTown

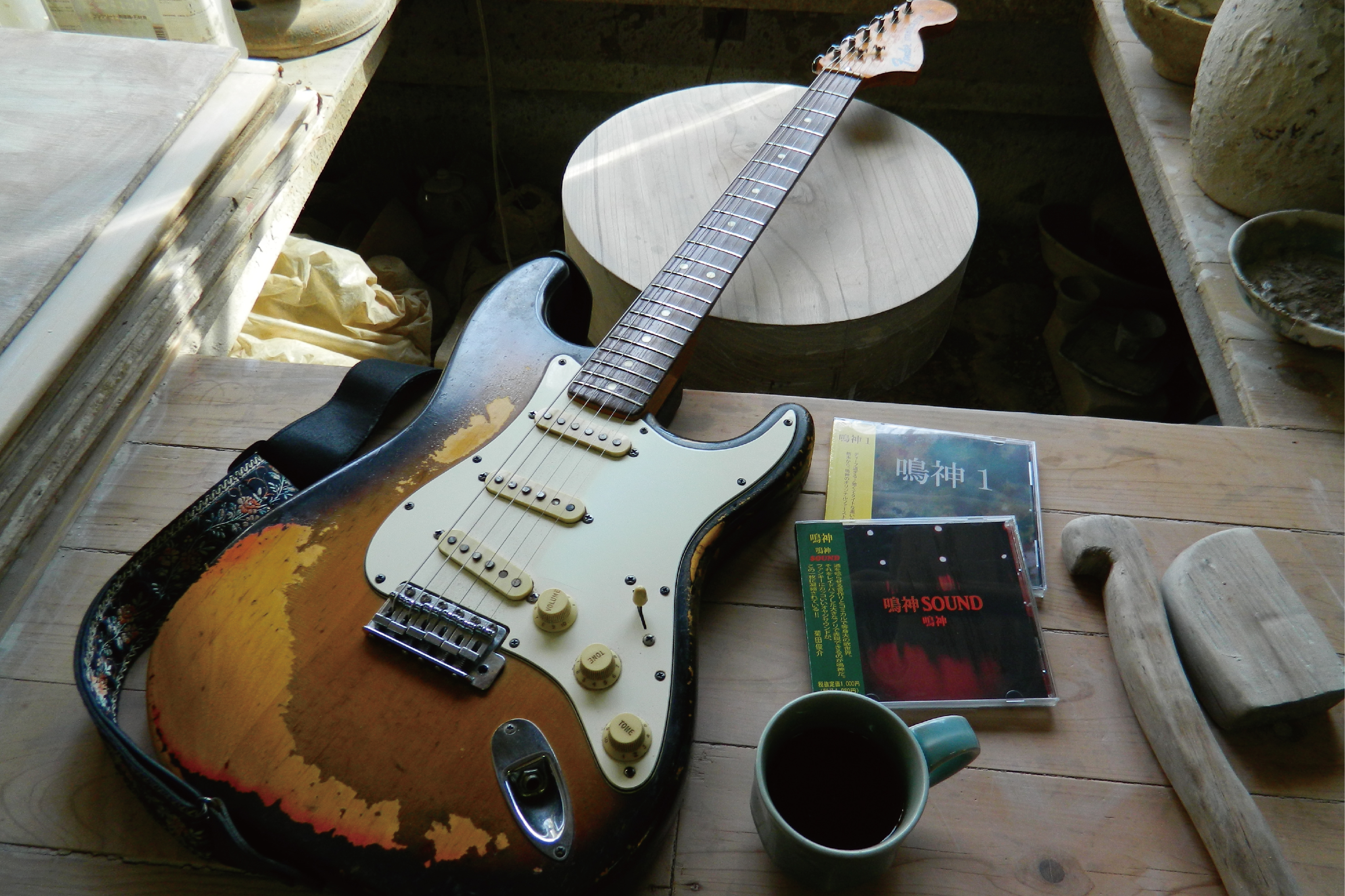

He has been making pottery for the last thirty-six years. Though Yukihiro Ohta is a leading ceramicist, he is also a blues guitarist. Together with the band Narukami, he has released three CDs. His pottery is appealing not only for its beautiful form but also for the vigor and vitality it expresses so thoroughly. When he creates his pieces, he turns his potter’s wheel with a rhythm not unlike a musical performance. Located amidst the mountains of Mashiko, Mr. Ohta’s studio hosts a near-daily live demonstration of the art of creating ceramics.

—Could you tell us about how you came to be a potter?

Ohta: When I was young, I wanted to be a musician. I had the naïve idea that if I went to Tokyo, I could do it! My father worked for Japan National Railways, but he loved painting and often painted pictures. Partly because of that, I also liked painting and I decided to go to an art university in Tokyo. My father said, “You won’t make a living painting. Go to an economics school! You can move to Tokyo if you study economics.” So, I decided to attend Tokyo Keizai University. One day, an acquaintance invited me to an underground studio at Nihon University, where students aiming to be pros were putting on a performance. I was surprised. Tokyo really was on a different level! Seeing a performance by such skilled performers, I gave up on music for a while, thinking I had no talent. After I graduated, I had to get a job. I joined a company on an acquaintance’s recommendation, but, for various reasons, I quit within a day. So, as I was worrying about what to do next, someone I knew got in touch with me, and I ended up working as the manager of a jeans shop in Shibuya. At the time, I was into American culture and music. I was also going regularly to a place in Koenji that played blues music and where illustrators and photographers tended to gather. At the time, I thought, “All these people have careers. All I am is the manager of a jeans shop. I can’t do anything. This sucks. I have to do something!” Actually, I met my wife then. One day, though we hadn’t filed our registration yet, my wife happened to visit the place of a potter friend in Mashiko. At that time, we met with that friend’s teacher, Tsuneo Narui, and my first impression of him left a real mark on me. He held his trousers up with a coarse rope—I thought, “Wow, that’s sharp!” And he told me all sorts of interesting things about pottery. In Iwate Prefecture, where I was born and raised, porcelain was the mainstream and there wasn’t any earthenware. So, I became really interested in ceramics. That, and I happened to see another potter eating steak and drinking red wine. I thought, “Maybe a potter can make money after all?” And that might be another reason I became a ceramicist.

—When did you move to Mashiko?

I made the move when I was twenty-six. I wanted to become a potter, so I started attending classes in Tokyo. An acquaintance of mine, a potter from Mashiko, told me, “Anyone can do pottery. Studying in Tokyo is a waste. You should come to Mashiko.” So, I resolved myself to becoming a potter in Mashiko. At around that time, I formalized my marriage to my wife and then relocated. I borrowed a truck from the proprietor of the blues club I had been a regular at to haul my things.

Well, I moved there, but I still didn’t know anything about pottery. So, I went to give my regards at Tsuneo Narui’s place, and he said, “For starters, go to my older brother’s pottery workshop and get some experience.” At the time, his brother was running a workshop there, and while I worked there, I would go to Mr. Narui’s place in the evenings to learn. That went on for about two years, until one of the senior students at Mr. Narui’s said, “You won’t get any better unless you come during the day.” So, I promised I’d do that, and studied for another year. At the time, it was typical to go independent after three years, so I started searching for some land to set up my own kiln. I was shown this place where I’m still producing pieces today, but I didn’t have money then.... I wanted to borrow money from a bank, but I didn’t have a guarantor, so even that was difficult. Then Mr. Narui said he would be my guarantor. There was a place on the paperwork for the loan where I had to write what his relationship was to me, and I asked him, “Are you my teacher?” He said, “Write ‘friend’ there.” He was a unique individual, to be sure.

—Once you became independent, were you able to get work right away?

Ohta: At first, I had a hard time selling. When I went to a pottery village and showed my pieces, I was told, “This person sells for ¥200, so yours is maybe ¥180.” I went to the co-op center where pottery was sold, and as I hung around there, certain people would buy my pieces. And I sold quite a lot at the pottery market held twice a year. From the 1980s to the 1990s, there were a lot of shops that carried pottery in the metropolitan area, and I sold a lot during that time.

—What do you think is the appeal of Japanese pottery?

Ohta: Having worked at a jeans shop when I was younger, I liked secondhand clothing and music from the US, and I was heavily influenced by the idea of Made in the USA. But when I started making pottery, I became aware of the incredible depth of Japanese pottery. In ancient times, China was the advanced country in terms of pottery, but now it’s Japan probably. Japanese pottery is used in daily life, yet you can perceive a beauty to it. Mr. Narui said to me, “Anyone can make a tea bowl, but it’s difficult to make a good one.” The tea bowls he makes are less than 15 cm wide, but on the inside there’s an infinite world. I work hard every day to see if I can make a tea bowl like that. It’s been thirty-six years, but it’s still quite difficult.

The technique for typical pottery is to form the clay with your fingers and smooth it with potter’s ribs. Tsuneo Narui taught me that when I push the clay in at its center, it will move and take shape. It’s not about making the shape so much as moving the clay. It’s not something I’m able to do just because I’ve been doing it for a long time. My ideas and state of mind at the time have various effects. My goal is to pull the clay into shape all at once, without leaving any excess, but it doesn’t necessarily work out so well. I use a kick-wheel instead of an electric potter’s wheel, and I’m not sure I could do it without the kick-wheel. I have my own particular timing. I’m not saying it’s because I do music, but in a sense, it’s similar to a session with the band. Do you know about the concept of playing “in the pocket,” in traditionally Black forms of music like jazz and blues? In the second and fourth beat, there’s a rhythm known as a backbeat, and if the players are together on that rhythm, they feel like they could keep on playing forever. When I’m spinning my kick-wheel and I perceive that rhythm, I feel like I’m getting close to making pieces that satisfy me.

—Finally, can you tell us about the appeal of Mashiko ware?

Ohta: In the present day, it’s unbelievably difficult to even define Mashiko ware. There’s no clear definition like there is for Bizen ware. In a certain sense, Mashiko ware is an arena of unrestrained competition. It’s a virtue of Mashiko that it will accept any kind of piece by anyone. The only thing I can say for certain is not allowed is copying. It has to be your own original work. Between that and Japan’s long tradition, I think it’s better to create based on concepts derived from Japanese tradition. I’m not comfortable with incorporating European tableware motifs willy-nilly, just because European tableware is trendy right now. What about the wonderful culture of Japan, rooted in its natural features? I think it’s preferable to look to Japan’s natural features for motifs when creating pottery, in order to sustain its culture for the future.

Profile

1955: Born in Morioka, Iwate Prefecture

1981: Relocated to Mashiko, Tochigi Prefecture, to study under Tsuneo Narui

1985: Built his climbing kiln in Ichinosawa in Mashiko, Tochigi Prefecture

Since then, he has won numerous awards.

In addition to being a ceramicist, he is a prolific musician (blues guitarist).

He has released three CDs.

Click here for the video being played

For inquiries to potters, please contact the following email address

For inquiries to artists, please contact the following email address